Introduction

Language models don’t “think” in the human sense. They don’t muse, reflect, or stew over questions. Instead, they predict. At their core, large language models (LLMs) like GPT operate on a principle that’s deceptively simple: given some input text, what’s the most likely next word? Let’s pull back the curtain to explore how LLMs generate responses that seem almost human—and what’s going on under the hood when they do.

Breaking Down the Process

Imagine a huge library. Each book in this library represents a snippet of human conversation, a blog post, a news article, or a novel. When you ask an LLM a question, it’s as if the model races through this library and begins assembling a new page—one letter, one word at a time—based on patterns it learned from reading every book in the collection.

The key is that the LLM doesn’t create this new page out of thin air. Instead, it relies on a mathematical understanding of word relationships. It knows that in English, certain words follow others more frequently. For instance, if you write,

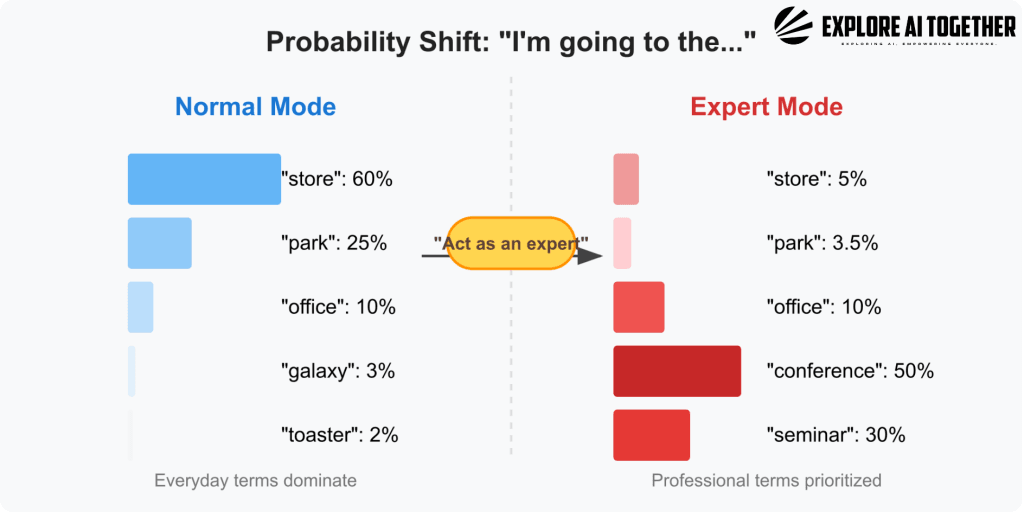

“I’m going to the,” the model has learned from vast amounts of text that words like

- “store” or

- “park” or

- “office”

are far more likely to come next than

- “galaxy” or

- “toaster.”

The AI is “thinking” something like:

store: 0.6 (60% likely)

park: 0.25 (25% likely)

office: 0.1 (10% likely)galaxy: 0.03 (3% likely)

toaster: 0.02 (2% likely)

So tell the AI to “Act as an expert” – which weirdly works… here’s how and why that happens.

When we tell the AI to “act as an expert,” it essentially shifts its internal probabilities toward words that better fit the requested context. In our original example, the general-purpose prediction for “I’m going to the…” might lean heavily toward “store” or “park” because those words are more common in everyday language.

However, if we instruct the model to think like a medical professional or academic, those odds recalibrate. The AI “knows” from training that experts tend to use certain terms more often, so now “conference” or “seminar” might become 50% and 30% likely, respectively, while words like “store” drop down to 5%.

This dynamic adjustment of probabilities is why a simple prompt like “act as an expert” can so dramatically change the tone and content of the response—it’s not that the AI gains knowledge it didn’t already have, but rather that it reweights what it already knows to prioritize a more specialized vocabulary and phrasing. This shift gives the impression that the AI “understands” the role it’s playing, even though it’s really just recalculating which words are statistically most appropriate.

Inside the Model: Layers of Understanding

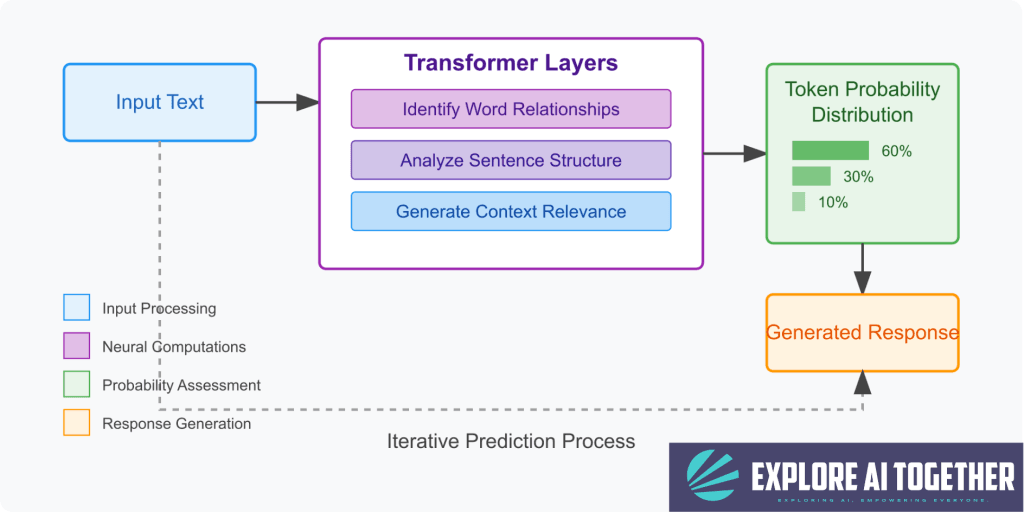

To generate a response, the LLM passes your input through a series of layers, each designed to refine its “understanding” of context. These layers are part of a neural network, which is essentially a web of interconnected mathematical nodes. Each layer helps the model:

- Grasp the meaning of your input by looking at individual words and their relationships.

- Analyze the overall structure of the sentence and the tone you’re using.

- Consider what’s most relevant or coherent to say next.

- Predict the next token (a word or piece of a word) and then repeat this process step by step until a complete response is formed.

Diagram: The Flow of a Thought

Why It Feels Like Thinking

What makes this process so fascinating is that when you interact with an LLM, you’re seeing the result of billions of calculations distilled into a coherent response. It’s not thinking, but it’s also not entirely random. It’s the result of patterns learned from human language—patterns that mimic reasoning, recall, and creativity.

When an LLM responds with insight or humor, it’s because those same patterns appear in the vast data it was trained on, not because the model itself is “aware” of what it’s saying.

Conclusion: Beyond the Illusion

LLMs operate in the space between mechanics and magic. They don’t feel, think, or plan the way we do, but they can echo the structures of human thought so convincingly that we’re tempted to attribute intelligence to them.

By demystifying their process, we see that the real marvel isn’t that they think like humans, but that a structured cascade of probabilities can produce such fluent and engaging responses that appear as “intelligent.” Perhaps we’ve unlocked something about our understanding of our own thought process.